Welcome to another Exploring with a Camera! This week I’m exploring the “Rule of Thirds,” looking at how this rule works and when to break the rule.

The Rule of Thirds is simple:

1. Divide your frame into thirds horizontally and vertically.

2.When framing your image, place your subject on one of the lines or intersections created by the thirds.

The Rule of Thirds is a guiding principle that can help you create interesting visual compositions. Calling it a “rule” is a complete misnomer – it’s no more a rule than any other compositional principle. It is more of a suggestion, an idea to keep in mind while your create. Composition is a complex subject and relies on so many aspects working together, you can’t just state one principle as a “rule” to be followed all of the time.

As I’m taking or cropping photographs, I don’t actively think about applying the Rule of Thirds or any specific compositional principle. I use my eye to gauge what might be a good composition, which takes into account all of the different things going on in each individual photograph. I experiment with various compositions of the same subject. It is interesting for me to see, after the fact, what principles I might have unconsciously applied. This type of review helps me to understand where the principles do and don’t work for me, which in turn will help me create better images the next time I go out and shoot.

If you are new to photography and trying to learn composition, thinking about the Rule of Thirds as you shoot or crop can help you see how it works and where you might successfully use it in your images.

I’m going to go through a number of examples that consider the Rule of Thirds to see whether an image follows the rule exactly, partially or not at all. It was an interesting exercise for me, because it was more difficult than I thought to define if an image partially followed the rule or broke the rule. Here are the definitions that I came up with:

- Following the Rule of Thirds: If the focal point (main subject) of the image falls exactly on a third line or intersection, it follows the rule.

- Partial use of the Rule of Thirds: If the focal point is close to a third line or intersection and has the appearance of following the rule, it partially follows the rule.

- Breaking the Rule of Thirds: If the focal point is nowhere near a third line or intersection and doesn’t have any appearance of following the rule, it breaks the rule.

I’ve applied a grid divided into thirds to all of the images to help you visualize the rule applied to each example. You can learn how to apply a grid set to thirds in Photoshop Elements with instructions

here, or Ashley of

Ramblings and Photos posted a video for Photoshop (very similar to Elements) in her post

here. If you use other software, do a web search for your software. (Note: When you apply a grid in software you won’t see it when you save or print your image, it’s only viewable while using the software. I had to work some special magic to create these examples showing the grid lines.)

Following the Rule of Thirds

In general, I discovered that I follow the rule most exactly with simple images. Images where there is a single subject and a consistent background are a great place to use the rule of thirds.

This abstract image from Burano is a good example of following the third lines. It is very simple, looking at the different textures and the light on the surfaces. Applying the Rule of Thirds makes an interesting composition out of what could be a very boring subject.

This image of flowers on the table is a great example of putting the main part of the subject at the intersection of two lines. The whole plant is the focal point, on the right vertical third line, but the flowers are the focal point within the focal point, and they are closest to the intersection.

The image of the path and trees is more complex, but the break in the trees falls on a third line exactly, creating a place for your eye to follow down to the people. Note that the people and horizon are not on the horizontal third line but are positioned lower, which helps emphasize the height of the trees. If they were exactly on the lower horizontal third line, it would have emphasized the people and the path.

I loved how my crop of this image came out exactly on the rule of thirds. The main subject, the woman walking out of the building, falls on an intersection of third lines. The reflections trail away along the horizontal line. There is a lot going on in this image to explore, but the rule of thirds works very well here.

Partially Using the Rule of Thirds

When I was writing my

Find Your Eye lesson on composition, I discovered that some of my images have the appearance of following the rule of thirds, but the subject is really not on a third line or intersection. This is a great thing to discover! You can get great compositions using this principle without being precise.

I truly thought this image of a leaf on wet pavement followed the rule of thirds. That’s what I was going for when I cropped it. Look how far off it is from the intersection! This goes to show that balance of the elements – the leaf versus the pebbles and reflections – comes into play as well as the rule of thirds.

This picnic table in this image has the feeling of following the rule of thirds to me, but it is not on the intersection. Again, balance of the elements in the image was more important than exactly following the rule of thirds.

My favorite happy image of flowers from Barcelona seemed like it followed the rule of thirds, but the focal point flowers are much more centered that I realized. It still works!

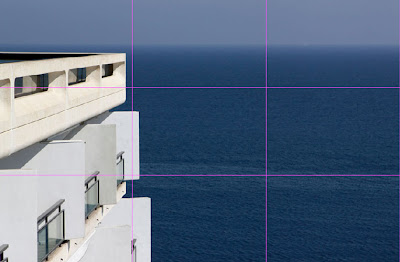

Along with the rule of thirds, you may often hear, “Put the horizon on one of the third lines.” While that works in principle to help you create more interesting compositions, it doesn’t always apply. This image from Monaco has much of the visual weight, from the bright white of the building, in the left third of the image. The horizon line doesn’t need to be on the third line here for a good composition.

Breaking the Rule of Thirds

Many, many images have no relation to the rule of thirds and yet still have a great composition. Applying the grid lines you might see some elements that line up, but the subject and composition don’t follow the rule of thirds at all. Just remember that the “rule” of thirds was meant to be broken!

The lead in photo, from my recent

photo excursion with Kirstin, shows a composition that has nothing to do with the rule of thirds. One element happens to line up on a third line, but that is just coincidence. The image is composed mainly to highlight the lines and color.

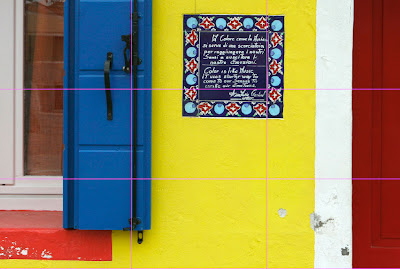

The ceramic plaque in this photo below from Burano is more centered than on any third lines. The composition was created to capture the plaque in relation to the elements surrounding it, the window and the door, and their relative colors.

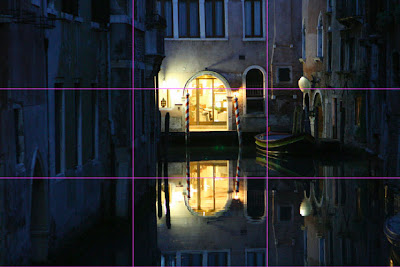

In one of my all time favorite images of Venice at night, I can’t find any relationship to the rule of thirds.

Here we have a simple image on a plain background, which could be perfect for the rule of thirds, but I opted to fill more of the frame. The subject is off center for a more pleasing composition, toward the bottom third intersection, but that’s about the only relationship to the rule of thirds.

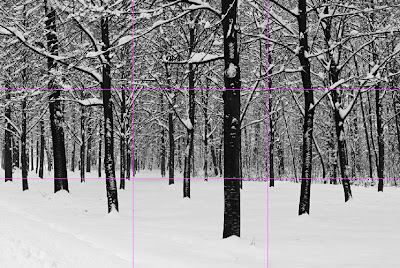

The subject here is the trees and the patterns they make. None of the dominant trees fall on the third lines or intersections. The only relation to the rule of thirds is the horizon line happens to be near the bottom third line.

The subject in this image from Bologna is the bicycle, which is nowhere near an intersection or line. The interesting thing is that the more complex or detailed parts of the image, the visual “weight,” fall in the bottom and right third parts of the grid. The image breaks the rule of thirds in terms of my definition of focal point, but the principle of thirds still influences the composition. This example shows composition is a complex topic!

Now, it’s your turn!

I hope you’ve enjoyed this exploration into the rule of thirds. Now, it’s your turn to take a look at your photos with an eye to this principle and see how it works or doesn’t work for you. Link in your images and be sure to put a comment on whether the image follows, partially follows or breaks the rule. All images, archive or new, are welcome. I would love it if you would share my Exploring with a Camera button if you participate – you can find it

here.

It’s so much fun to give things away, I’ve started collecting fun little giveaway items in addition to my postcards. This time I’ll be giving away this “C is for Camera” blank notebook I picked up in London. The winner will be drawn at random from those who link an image in below.

Thanks for participating! I can’t wait to see what interesting images you have to show this time.